Car makers are increasingly focusing on the environmental impact of making EVs. While necessary, such efforts could slow the technology’s adoption.

By Stephen Wilmot

Auto makers need to ensure their electric vehicles are actually green. They also desperately need to bring down their cost. Pursuing both goals at once is hard.

The all-electric technology popularized by Tesla involves a kind of front-loading of environmental risk. EVs emit less carbon than a conventional car, even when recharged with electricity made by burning coal, but their powerful batteries require a lot of resources to make.

This inconvenient truth is one reason car makers are getting more involved in the EV supply chain. Investments such as the new battery factories announced by General Motors this week are mainly about securing greater control over the supply, technology and costs of the most important EV component. But a fourth factor fast rising up the priority list is control over their environmental footprint.

Buying battery cells made with renewable electricity is one focus. Faced with very strong demand, European battery startup Northvolt, which is backed by Volkswagen and BMW among others, last week raised $2.75 billion to further expand its low-carbon production facility in northern Sweden, where hydroelectric power is plentiful.

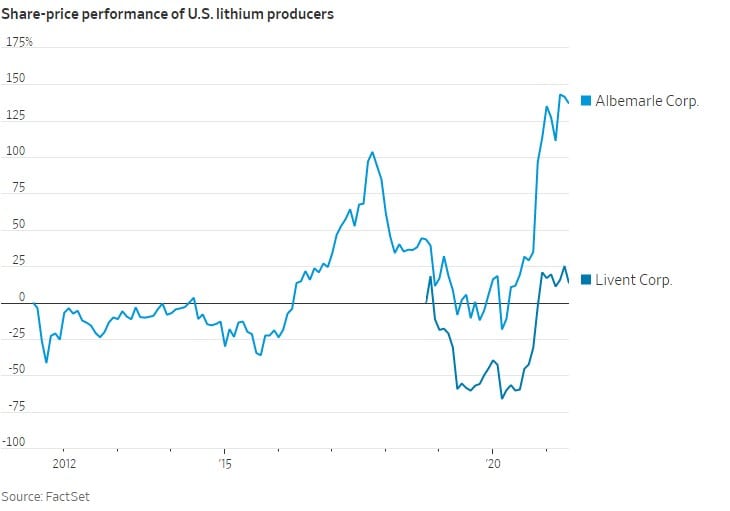

Another hot topic is the mining of battery metals, notably lithium. The industry used to worry more about cobalt, which is sourced mainly from the Democratic Republic of Congo amid charges of child labor, but in recent years the metal’s role in battery chemistry has shrunk. Lithium can’t so easily be minimized in lithium batteries. The stocks of U.S. producers Albemarle and Livent are trading close to record highs.

Auto makers Volkswagen and Daimler, German chemical giant BASF and smartphone maker Fairphone last week formed a “responsible lithium partnership” to protect the area in Chile that produces much of the global supply. Earlier this year BMW signed a $335 million “sustainable” supply deal with Livent, which mines in neighboring Argentina. The big environmental question for Andean lithium miners is how much water they use and how it impacts water supplies for the local community.

Focusing on how mass battery production affects the planet makes complete sense given the largely environmental reasons for scaling up the technology. However, it necessarily comes at a price. Extracting cost reductions from the battery supply chain, which is necessary to make EVs more affordable, becomes harder and slower if auto makers limit themselves to metal supplies they can certify.

Because lithium batteries spread around the world in mobile phones, it is sometimes mistakenly assumed they are subject to the same deflationary trends as the microelectronics industry, which has thrived amid the global abundance of silicon for semiconductors. Batteries are an industrial product highly dependent on metals that, while mostly not rare, will take time to get out of the ground responsibly at scale.

“The data is pointing to the battery cost curve coming down much more slowly than hyped. There are a lot of bottlenecks and challenges that people are ignoring,” says Mio Kato, an analyst who publishes on research platform Smartkarma.

Wealthy consumers might continue to adopt luxury EVs, but in the absence of generous subsidies it is hard to see the technology taking over much of the mass market until they are cheaper than traditional cars. Many forecasters currently expect that to happen around the middle of this decade. The need to keep EVs green is, ironically, another reason why such hopes might prove optimistic.

“The data is pointing to the battery cost curve coming down much more slowly than hyped. There are a lot of bottlenecks and challenges that people are ignoring,” says Mio Kato, an analyst who publishes on research platform Smartkarma.

Wealthy consumers might continue to adopt luxury EVs, but in the absence of generous subsidies it is hard to see the technology taking over much of the mass market until they are cheaper than traditional cars. Many forecasters currently expect that to happen around the middle of this decade. The need to keep EVs green is, ironically, another reason why such hopes might prove optimistic.

“The data is pointing to the battery cost curve coming down much more slowly than hyped. There are a lot of bottlenecks and challenges that people are ignoring,” says Mio Kato, an analyst who publishes on research platform Smartkarma.

Wealthy consumers might continue to adopt luxury EVs, but in the absence of generous subsidies it is hard to see the technology taking over much of the mass market until they are cheaper than traditional cars. Many forecasters currently expect that to happen around the middle of this decade. The need to keep EVs green is, ironically, another reason why such hopes might prove optimistic.

Write to Stephen Wilmot at stephen.wilmot@wsj.com