A shortage of parts and technicians, more complex auto technology, and older cars on the road are creating a perfect storm; Ford and GM are concerned

By Nora Eckert

Ronnie Clendenin has been working in the auto-repair business for three decades. He’s never been so frazzled.

The parking lot at Clendenin’s Tire and Auto Service in Guy, Ark., a town about an hour north of Little Rock, was recently packed with 62 vehicles, double the typical workload from a few years ago. Without the workers or car parts he needs to keep up, Clendenin says, he regularly turns away loyal customers.

“It’s hard to do. People aren’t used to it,” he says. “They’re used to just dropping it off and getting it taken care of.”

Across the U.S., a shortage of car parts in the past few years has collided with a continuing dearth of service technicians. The result: more frustrated customers, who are waiting longer to get their cars back, and paying more for service.

The backlog risks becoming a drag on the U.S. economy as higher repair costs prompt consumers to cut back spending elsewhere, or simply not having a working car curtails their mobility and productivity. A swath of service industries are facing labor shortages, from home construction to restaurants, appliance repair to trucking.

For the big automakers, this is the latest sign that the industry is still struggling to adapt to the shifts from the last few years. Nearly everything about shopping for and owning a car is different since the Covid-19 pandemic: Americans wait to get the car they want instead of driving it off the lot, they have fewer choices, and discounts or cheap leases are a thing of a past, prepandemic life.

The average auto repair took more than 17 days to complete last year, up around 65% from 10.3 days in 2019, according to a study from CCC Intelligent Solutions, a technology and AI provider for insurance and automotive clients.

When Oliver Swan got a flat tire on his BMW iX xDrive50 EV after driving over a razor blade, he tried BMW dealers from Arizona to New Jersey. He was told his replacement tire would take at least a month to arrive. In the meantime, he drove a loaner car from the dealer. When the dealer pushed that one-month date back, Swan decided to contact the company and tire supplier himself.

“Something as simple as a stupid tire wasn’t really in stock,” said Mr. Swan, a 43-year-old real estate investor in Tucson, Ariz. He wrote emails to executives at the tire supplier and to BMW, and eventually received a replacement about a month after he got his flat.

A BMW spokesman said almost all parts ordered by BMW dealers are able to be delivered overnight. The company isn’t aware of any delays in tire availability for the BMW iX, he said.

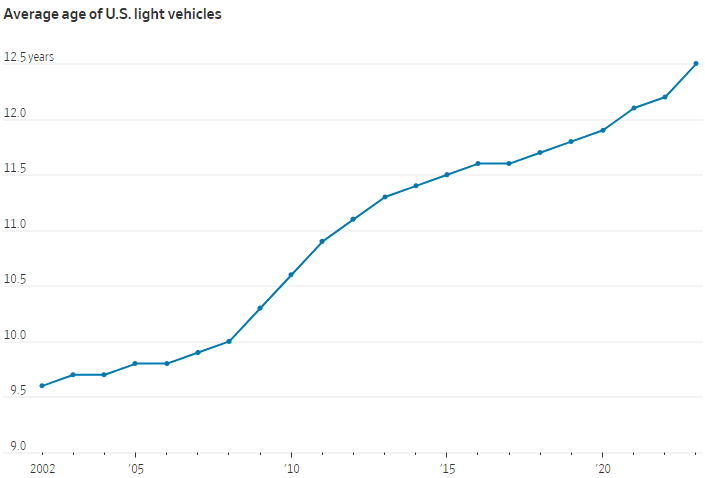

Another factor driving demand for car repair: Owners are clinging to their aging vehicles longer, in part due to the sharp rise in prices for new and used vehicles since the pandemic, dealers and analysts say. The average age of a vehicle on the road in the U.S. hit a record 12.5 years in January, a trend that has stoked greater demand for repair work, according to a report released in May by S&P Global Mobility.

That has customers willing to spend more on repairs than they have in the past, shop owners say. The average cost of a repair increased 19.7 percent over the last year, while maintenance and service was up 9.9%, according to May data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index for urban consumers.

Dealers and independent mechanics describe a frustrating situation: Demand is booming, but many shops are missing out on business because they lack the staff to keep up.

The situation has even prompted car companies to try to help their independent dealers solve the problem. Ford Motor and General Motors are among automakers funneling money into tech-training programs and scholarship funds.

A lack of qualified workers has been a problem across the industry for more than a decade. There is a need for 258,000 new automotive technicians annually, but just 48,000 people graduate from tech-training programs each year in the U.S., according to TechForce Foundation, a workforce-development group.

Dealers, repair shop owners and auto executives point to several causes. Some say the proliferation of computer-based jobs over the last two decades has sapped enthusiasm for skilled trades. Others say technicians haven’t been paid enough over the years to stick around, and that the often back-breaking work has become less enticing for younger people.

Repair workers also n

The average weekly wage for U.S. automotive repair and maintenance workers increased 24.3% to $1,003, in the fourth quarter of 2022, from the same period in 2018, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That outpaced the increase in median weekly pay for all U.S. workers during the same timeframe, which rose 21% to $1,084.

Kyle Teuscher, a 24-year-old technician at a dealership in Michigan, wanted to work on cars ever since he was little, when he spent late nights repairing old Jeeps with his grandfather and dad. He knew the career would be physically demanding, but saw it as a lucrative line of work to jump into after high school.

Already, though, the job has gotten tougher. There aren’t enough techs in his service department, so Teuscher and his co-workers have to shoulder more of the work.

eed to undergo frequent training because vehicles have increasingly sophisticated electrical and computer architecture, presenting problems that can sometimes flummox even experienced technicians.

“I’m definitely more worn out at the end of the day,” Teuscher said.

Customers have also come in with more time-intensive jobs recently, he said. That’s partly because the cars are trending older, but Teuscher also grapples more with finicky technology on newer cars that can be difficult to diagnose, such as glitchy multimedia touchscreens.

For the technician, who makes the bulk of his pay on a per-job basis rather than an hourly wage, this can translate into making less money at the end of the day.

To retain techs like Teuscher, some dealerships and repair centers have offered more flexible work schedules, sweetened benefits and significantly higher pay.

Some service managers say the competition for good service techs is stiff, and they are taking steps to prevent their people from getting poached.

At Bowman Auto Group in Michigan, the Chevrolet dealership removed its technicians’ names from its website. Service managers noticed some visitors snapping pictures of mechanics’ names on their licenses on the wall, which it figured was for recruiting purposes. The dealership repositioned a display in the customer lounge so that names and license numbers are partially blocked.

“The war is on, and you’ve got to be smart about it,” said Rhonda Jensen, the group’s general manager.

Over the last few years, the dealership has spent $1.5 million to upgrade the service shop in part to make it more comfortable for workers, with new flooring and walls, an upgraded lounge and better lighting, Jensen said.

The car companies have an interest in helping their dealerships solve the service bottleneck. As they roll out more electric vehicles, the carmakers are relying on their networks of thousands of dealership service centers to emerge as an advantage over Tesla, Rivian Automotive and other newer rivals that don’t have franchise dealers.

Ford, for example, has been working with its dealers in recent years to expand a complimentary mobile-service operation that can offer oil changes, tire rotations and other repairs at customers’ homes, said Elena Ford, the company’s chief customer experience officer, who is a descendant of Henry Ford.

“Customers really are asking to be serviced in a more simple way,” she said. “We’re meeting them on their terms.”

In March, the Dearborn, Mich.-based company said it would invest $1 million in a scholarship program for students working to become auto technicians. It focused on four markets: Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas and Phoenix.

GM also has invested in programs that train technicians, including sponsoring students at community colleges and providing retention incentives for GM technicians.

“We’re looking at being able to support our customers how and when they want,” said David Marsh, GM’s executive director of sales and marketing for aftersales. “You can’t do those things without a strong technician base.”

Meanwhile, lingering supply-chain choppiness throughout the auto industry has pinched inventories of key components at repair shops, from computer chips to tires.

Factory shutdowns during the pandemic stalled production of semiconductors, which are integral to car systems such as blind-spot detection and automatic braking. While the computer-chip shortage has eased, other supply-chain and logistical snags continue to plague dealership parts departments, dealers say.

“The chip shortage right now is more disruptive to profitability, but it will eventually end,” said David Whiston, analyst for Morningstar Research Services. “The technician shortage is probably going to be around for a long time.”

For Swan, the long wait for his BMW’s tire replacement caused him to gear up for future delays. He ordered a couple of backup tires. They took a few weeks to arrive.